Table of Contents

- Java Optional: 1. What is null?

- Java Optional: 2. Introduction to Optional

- Java Optional: 3. Intermediate Optional methods

- Java Optional: 4. Terminal Optional methods

- Java Optional: 5. A closer look at Optional

The birth of null

null first appeared in 1965 when British computer scientist Tony Hoare designed ALGOL W.

At that time, he considered null reference the simplest way to represent “no value.”

But in 2009, at a software conference, he called null reference his “billion-dollar mistake” and apologized. Although easy to implement, it led to countless errors, vulnerabilities, and system crashes with huge cost.

What exactly makes null reference so problematic?

About null

Before discussing the pain null causes in Java, let’s define what null is.

null is a Java keyword

null is a case-sensitive keyword like private and final.

So it cannot be written as Null or NULL; only null is valid.

null and reference types

null is the default value of reference types.

Just as primitive types have default values,

reference types have null as default.

For example, primitive boolean defaults to false, and int defaults to 0.

That does not mean null is a separate data type like primitive/reference types.

It is a special value assignable to all reference references.

Even casting works as below, though both still reference null.

String str = (String) null;

Integer val = (Integer) null;

null is valid only for reference types.

Assigning it to primitive type variables causes compilation errors.

int value = null; // compilation error

null and auto-boxing

When wrapper references like Integer or Double point to null,

unboxing to primitive types causes NullPointerException.

Because this is not obvious at compile time, care is required.

Integer BoxedValue = null;

int intValue = boxedValue; // NullPointerException

Auto-boxing/unboxing assumptions often make this easy to miss.

See another example using Integer keys in a map.

Map<Integer, Integer> map = new HashMap<>();

int[] numbers = {2, 3, 1, 5};

for (int num : numbers) {

int count = map.get(num); // NPE if `get` result is null

map.put(num, count++);

}

Map returns null when key is missing.

When that null is assigned to primitive type, NullPointerException occurs.

null and static

Calling methods on a null reference usually throws NullPointerException.

But if the method is static, no exception occurs and execution succeeds.

public class MyClass {

public static void sayHello() {

// ...omitted

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

MyClass myClass = null;

myClass.sayHello(); // reference is null, but no NPE

}

}

Static members belong to class, not instances. So compilers optimize calls at compile time into class-level calls.

Example with Thread:

Thread t = null;

// no NPE

// optimized as Thread.yield(); at compile time

t.yield();

So for static methods, calling through class names avoids confusion.

null and operators

Operators usable with null are limited.

Using instanceof with null reference returns false.

But relational operators (>, >=, <, <=) can trigger NullPointerException.

== and != are valid.

Problems with null

Why is null a problem?

null does not align with Java’s simplification philosophy.

If you used C, you know the difficult concept of pointer.

Java hides pointers from developers, except null.

A reference to non-existent value is itself a source of errors.

Overusing null references makes NullPointerException very easy to encounter.

When adding null checks to avoid exceptions, clean code quickly degrades. Indentation depth increases and readability drops.

NullPointerException

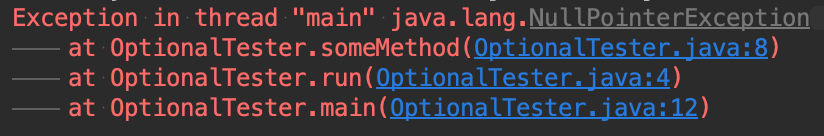

Most Java developers have encountered NullPointerException (NPE).

As shown, in Java null means absence of reference.

When code calls instance methods on null-referenced objects, NPE occurs.

The painful part is that NPE appears at runtime. So before execution, compile-time detection is hard.

Execution logs show failing line, so location is easy to find. But root cause still needs manual diagnosis. Java 14 “JEP 358: Helpful NullPointerExceptions” improves this somewhat.

NPE examples

Let’s review scenarios where NPE occurs.

Assume classes below.

Person has Phone field, Phone has Manufacturer, and Manufacturer has String name.

For brevity, getters/setters are omitted.

// Person

public class Person {

private Phone phone;

}

// Phone

public class Phone {

private Manufacturer manufacturer;

}

// Manufacturer

public class Manufacturer {

private String name;

}

And suppose this method exists. It returns “phone manufacturer name of a person”. Simple logic, but experienced Java developers can spot potential NPE.

If Person has no phone info and getPhone returns null, what happens?

NPE occurs.

getManufacturer is an instance method of Phone, so invoking it on null reference throws NPE.

Also, if input person itself is null, NPE occurs when attempting getPhone.

// returns phone manufacturer name

public String getPhoneManufacturerName(Person person) {

// if `person` is null?

// or if result of `getPhone()` is null?

return person.getPhone().getManufacturer().getName();

}

The risk does not end there.

Callers of this method can also hit NPE.

If getPhoneManufacturerName returns null, caller receives null and inherits potential NPE risk.

String manufacturerName = getPhoneManufacturerName(person);

// NPE may occur if manufacturerName references null

String lowerCaseName = manufacturerName.toLowerCase();

How can we protect code from this NPE risk?

Classic way to prevent NPE

Before Java 8 Optional, let’s review older NPE-avoidance patterns.

Typically, extra null checks were added like below.

public String getPhoneManufacturerName(Person person) {

if (person != null) {

Phone phone = person.getPhone();

if (phone != null) {

Manufacturer manufacturer = phone.getManufacturer();

if (manufacturer != null) {

return manufacturer.getName();

}

}

}

return "Samsung";

}

If deep indentation is disliked, code like below is used. Readability improves somewhat, but return statements spread across multiple exits. Multiple exits can make maintenance harder.

public String getPhoneManufacturerName(Person person) {

if (person == null) {

return "Samsung";

}

Phone phone = person.getPhone();

if (phone == null) {

return "Samsung";

}

Manufacturer manufacturer = phone.getManufacturer();

if (manufacturer == null) {

return "Samsung";

}

return manufacturer.getName();

}

Another approach is Null Object Pattern. Its core idea is avoiding keyword null by defining substitute objects.

Example: Create interface or abstract class, then implementations.

interface Messenger {

void send(String msg);

}

class Kakao implements Messenger {

@Override

public void send(String msg) {

// ... implementation omitted

}

}

class Line implements Messenger {

@Override

public void send(String msg) {

// ... implementation omitted

}

}

Now define a class for null object role. Unlike normal implementations, this one exists only to avoid NPE, so method body does nothing.

class NullMessenger implements Messenger {

@Override

public void send(String msg) {

// do nothing

}

}

How to apply it: Whether objects come from factory methods or DAOs, core point is never returning null. Return substitute object instead.

class MessengerFactory {

public static Messenger getMessenger(String name) {

if ( ... ) {

// return Messenger implementation matching condition

}

// when no result, return NullMessenger instead of null

return new NullMessenger();

}

}

// ... code omitted

Messenger messenger = MessengerFactory.getMessenger("KakaoTalk");

messenger.send("Hello");

What is the advantage?

No need to check whether returned value is null.

So code is free from repetitive nested null-check if blocks.

You can go further and handle null objects via singleton in interface as below. This avoids creating a dedicated null-object class.

interface Messenger {

void send(String msg);

Messenger NULL = new Messenger() {

@Override

public void send(String msg) {

// do nothing

}

};

}

Does null object pattern have only benefits? No. If developers forget existence of null-object class, checks can become more complex than direct null checks.

When new methods are added to interface, you must implement them in null-object classes too, which increases maintenance cost.

Then what should we do?

How should we handle null to write safer and cleaner code?

Java 8 added Optional, a new approach for handling null.

The next post introduces what Optional is.