What is the finalize Method

All classes in Java inherit several methods from the Object class, the top-level class. The finalize method, also called an object destructor, is one of those methods. It is a finalizer method called when garbage collection performed by the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) executes to prevent resource leaks. It performs cleanup work on resources that are no longer in use.

vs C++ Destructor

Java manages memory directly through the Java Virtual Machine (JVM). Therefore, developers don’t need to be heavily involved in releasing dynamic allocations. However, C and C++ languages are different. If developers don’t explicitly release allocations, memory leaks occur.

Consider C++ dynamic allocation and deallocation with the following example code:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

class ObjA {

private:

int id;

public:

ObjA(int id) {

this->id = id;

cout << "Call ObjA Constructor" << endl;

}

~ObjA() {

cout << "Call ObjA Destructor" << endl;

}

};

class ObjB : public ObjA {

private:

int id;

string name;

public:

ObjB(int id, string name) : ObjA(id) {

this->name = name;

cout << "Call ObjB Constructor" << endl;

}

~ObjB() {

cout << "Call ObjB Destructor" << endl;

}

};

int main(void)

{

/* Object created in heap area */

ObjB *obj = new ObjB(3, "madplay");

delete obj; /* Developer's explicit dynamic allocation release */

/* Of course, if you create an object like this, it's created in the stack area and automatically released. */

ObjB autoDeleteObj(3, "madplay");

return 0;

}

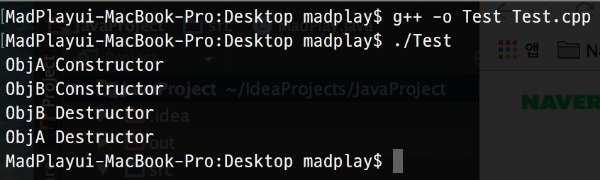

The above code was written in Mac OSX environment and compiled with gcc before execution.

Here we see a characteristic of C++ object creation and destruction. The destructor is guaranteed to be called.

If we convert the above code to Java, it looks like this:

class ObjA {

private int id;

public ObjA(int id) {

this.id = id;

System.out.println("Call ObjA Constructor");

}

public void finalize() {

System.out.println("Call ObjA Destructor");

}

}

class ObjB extends ObjA {

private String name;

public ObjB(int id, String name) {

super(id);

this.name = name;

System.out.println("Call ObjB Constructor");

}

public void finalize() {

System.out.println("Call ObjB Destructor");

super.finalize();

}

}

public class Test {

public static void main(String[] args) {

ObjB obj = new ObjB(3, "madplay");

obj.finalize();

}

}

In Java, the parent class’s finalizer is not automatically called, so you must explicitly call the parent class’s finalizer through super.finalize();.

If you run the above code, you can see why finalizers should be avoided. The book <Effective Java> mentions the following about using the finalize method:

As we saw above, Java’s finalize method does not guarantee execution. Performing operations like closing streams in such a finalizer method can be fatal.

class TestObject {

/* Stream variable, method declaration omitted */

protected void finalize() throws Throwable {

try {

if ( fileStream != null) fileStream.close();

} finally {

super.finalize();

}

}

}

Java Resource Release, null Assignment?

As mentioned earlier, it’s difficult for developers to carefully determine when to return memory. There is a method to request garbage collection execution, but it doesn’t guarantee execution.

/* Garbage collection is not guaranteed to run. */

System.gc();

If you look up Java memory-related materials, they recommend assigning null to objects that are no longer useful after use. What happens if you do that?

Consider Garbage Collection logs to see the difference based on usage. For example, in Eclipse, you can add -verbose:gc to VM Options.

- Method descriptions used

- Runtime.getRuntime().maxMemory() : The largest amount of memory the JVM attempted to use

- Runtime.getRuntime().totalMemory() : Returns all memory of the JVM in bytes

public class Test {

private static final int MegaBytes = 10241024;

public void resourceAllocate() {

long maxMemory = Runtime.getRuntime().maxMemory() / MegaBytes;

long totalMemory = Runtime.getRuntime().totalMemory() / MegaBytes;

System.out.println("totalMemory : " + totalMemory);

System.out.println("maxMemory : " + maxMemory);

byte[] testArr1 = new byte[2000000000];

System.out.println("### Second Allocation ###");

byte[] testArr2 = new byte[2000000000];

maxMemory = Runtime.getRuntime().maxMemory() / MegaBytes;

totalMemory = Runtime.getRuntime().totalMemory() / MegaBytes;

System.out.println("### Memory Allocation ###");

System.out.println("totalMemory : " + totalMemory);

System.out.println("maxMemory : " + maxMemory);

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

new Test().resourceAllocate();

}

}

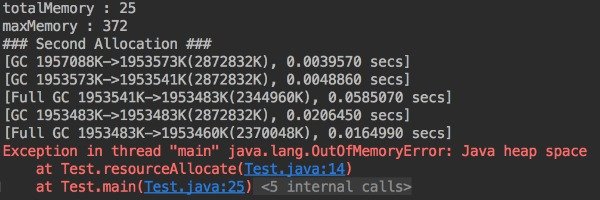

Running the above code results in the following OutOfMemoryError Exception.

Even after GC and Full GC occur, memory is still insufficient. This is because the reference to testArr1 exists until the resourceAllocate() method ends.

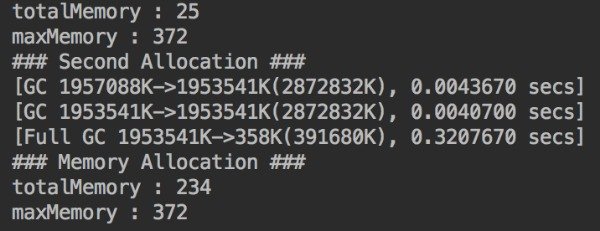

What happens if we assign testArr1 to null before allocating testArr2 in the above code?

...

byte[] testArr1 = new byte[2000000000];

/* Assign testArr1 to null */

testArr1 = null;

System.out.println("### Second Allocation ###");

byte[] testArr2 = new byte[2000000000];

...

You can see that the Out Of Memory Error exception does not occur. So, should we assign null every time after using an object for resource management?

For simple programs, it might be okay, but in large-scale programs, deciding where to assign null would be a concern. Null assignment has the disadvantage that once garbage collection occurs, it’s immediately reclaimed and the object can no longer be used afterward.

In such situations, there are ways to communicate more with garbage collection through the java.lang.ref package. For more details, refer to the following link.

Summarizing the relationship between garbage collection and the finalize method from the above link:

- Even after running garbage collection, if memory is sufficient, continue referencing. (Soft Reference)

- Continue referencing only until garbage collection occurs. (Weak Reference)

- Want to continue referencing even after the finalize method is called. (Phantom Reference)

Overriding in Inheritance Relationships

Despite the problems with the finalize method we saw above, if there is a custom class that overrides it and a subclass that inherits from this class and redefines the finalize method, it’s good to use a defensive technique that forces explicit invocation of the parent class’s finalizer when the subclass object is destroyed.

class ParentObject {

protected void finalize() {

/* Do Something */

}

}

class TestObject extends ParentObject {

private final Object finalizerGuardian = new Object() {

@Override

protected void finalize() throws Throwable {

/* Do Something... */

}

};

}

public class MadPlay {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Throwable {

TestObject obj = new TestObject();

obj = null;

System.gc();

}

}

We override Object’s finalize method through an anonymous class. When the TestObject object becomes eligible for garbage collection, member release and the finalize method are called.

If not using the above method, you can call the parent class’s finalize method from the subclass’s finalize method. However, there’s a possibility of forgetting to call the parent class’s method.

In conclusion, the finalize method does not guarantee execution. The benefits of using it are minimal. If you must use it, don’t forget to call the parent class’s finalizer. However, since it’s unpredictable, slow, and generally unnecessary, it’s more beneficial not to use it.

And in Java 9, the finalize method was deprecated and a new Cleaner class was added to the java.lang.ref package.

@Deprecated(since="9")

protected void finalize() throws Throwable { }

/*

* ... omitted

* @since 9

*/

public final class Cleaner {

// omitted

}