Creating Strings: new String(“Hello”) vs “Hello”

There are two ways to declare strings in Java:

String str1 = new String("madplay");

String str2 = "madplay";

The first uses the constructor with the new operator, while the second uses string literal syntax.

While they differ syntactically, they also differ in memory allocation.

When creating string objects using the new operator, they’re allocated in the Heap area of memory.

When using string literals, they’re allocated in an area called the String Constant Pool.

Note: The constant pool location was moved to the

Heaparea starting with Java 7.

Consider the following example:

String str1 = "madplay";

String str2 = "madplay";

String str3 = new String("madplay");

String str4 = new String("madplay");

str1 = str2;

// ... omitted

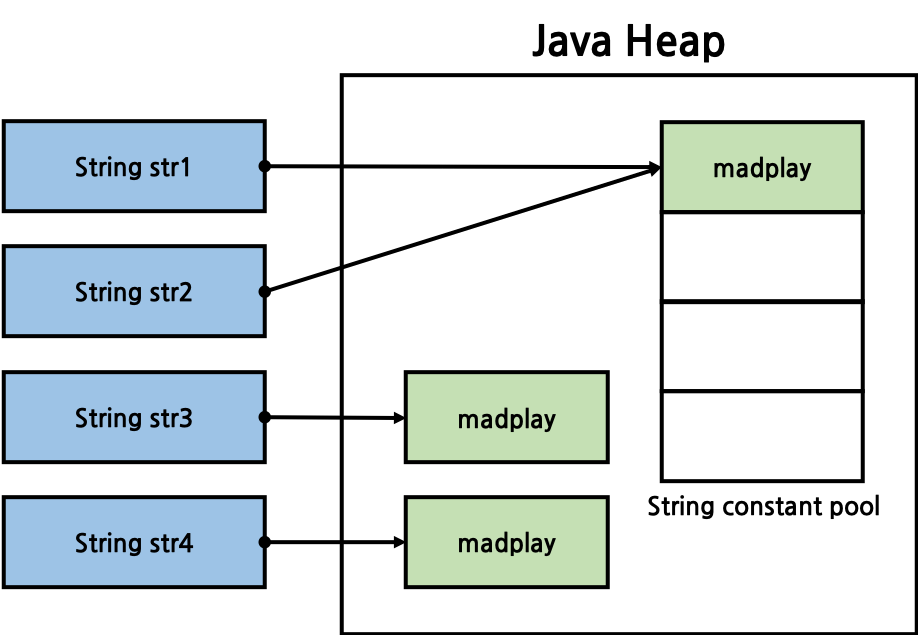

When mapped to the Java heap area, it looks like this. Strings created in the constant pool exist only once. Therefore, str1 and str2 reference the same string.

Conversely, when creating objects in the heap area, separate instances are created, so str3 and str4 reference different strings.

Comparing Strings: equals vs ==

Consider the following code that compares strings:

/**

* Compare String.

*

* @author kimtaeng

* created on 2018. 5. 12.

*/

public class MadPlay {

public static void main(String[] args) {

String someLiteral = "kimtaeng";

String someObject = new String("kimtaeng");

System.out.println(someLiteral.equals(someObject)); // print 'true'

System.out.println(someLiteral == someObject); // print 'false'

}

}

We declared the same string ‘kimtaeng’, but comparing with String’s equals method returns true,

while comparing with the == operator returns false. Why?

Examining String’s equals method reveals that it compares string values:

/**

* Compares this string to the specified object. The result is {@code

* true} if and only if the argument is not {@code null} and is a {@code

* String} object that represents the same sequence of characters as this

* object.

*

* @param anObject

* The object to compare this {@code String} against

*

* @return {@code true} if the given object represents a {@code String}

* equivalent to this string, {@code false} otherwise

*

* @see #compareTo(String)

* @see #equalsIgnoreCase(String)

*/

public boolean equals(Object anObject) {

if (this == anObject) {

return true;

}

if (anObject instanceof String) {

String anotherString = (String) anObject;

int n = value.length;

if (n == anotherString.value.length) {

char v1[] = value;

char v2[] = anotherString.value;

int i = 0;

while (n-- != 0) {

if (v1[i] != v2[i])

return false;

i++;

}

return true;

}

}

return false;

}

The == operator, on the other hand, compares object reference values. Therefore, reference values of strings created in the Heap area using the new operator and

strings in the String Constant Pool using literals cannot be the same.

Why?

Questions about differences between String’s equals and == operator are frequently asked in IT company interviews. (Though they seem less common these days…)

Understanding the operational differences is crucial.

For string literals, String’s intern method is called internally. From the Java API:

/**

* Returns a canonical representation for the string object.

* <p>

* A pool of strings, initially empty, is maintained privately by the

* class <code>String</code>.

* <p>

* When the intern method is invoked, if the pool already contains a

* string equal to this <code>String</code> object as determined by

* the {@link #equals(Object)} method, then the string from the pool is`

* returned. Otherwise, this <code>String</code> object is added to the

* pool and a reference to this <code>String</code> object is returned.

* <p>

* It follows that for any two strings <code>s</code> and <code>t</code>,

* <code>s.intern() == t.intern()</code> is <code>true</code>

* if and only if <code>s.equals(t)</code> is <code>true</code>.

* <p>

* All literal strings and string-valued constant expressions are

* interned. String literals are defined in section 3.10.5 of the

* <cite>The Java™ Language Specification</cite>.

*

* @return a string that has the same contents as this string, but is

* guaranteed to be from a pool of unique strings.

*/

public native String intern();

In summary, the intern method returns the reference value of that string if it already exists in the String Constant Pool,

otherwise it adds it to the pool and returns that reference value.

Consider the following code that compares strings using the intern method:

/**

* Compare String with intern method.

*

* @author kimtaeng

* created on 2018. 5. 12.

*/

public class MadPlay {

public static void main(String[] args) {

String someLiteral = "kimtaeng";

String someObject = new String("kimtaeng");

String internResult = someObject.intern();

System.out.println(someLiteral.equals(someObject)); // print 'true'

System.out.println(someLiteral == internResult); // print 'true'

}

}

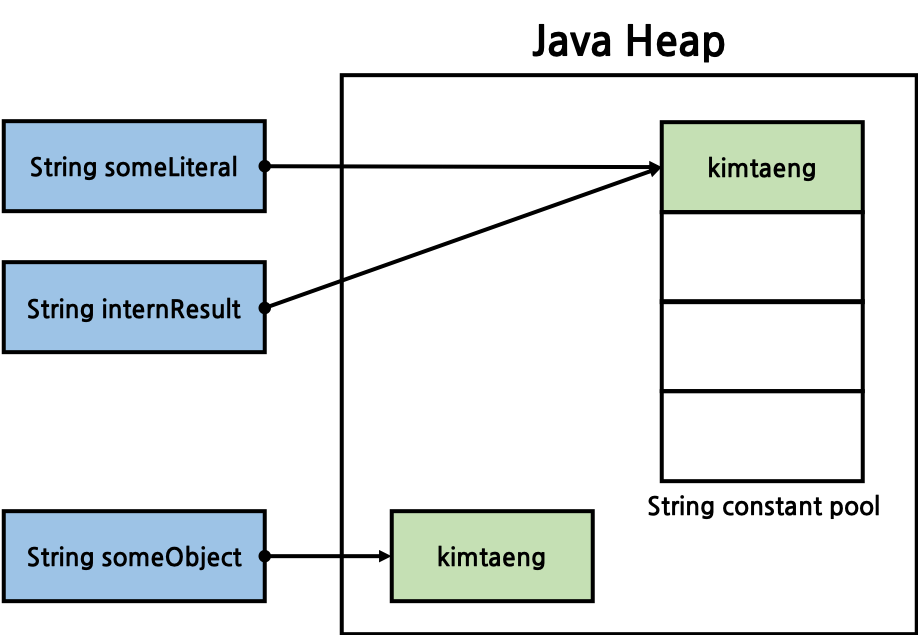

We see that when comparing reference values of String objects created using the new operator and String objects created with literals, they differ.

However, after applying the intern method to objects created with the new operator, the reference values match those created with literals.

As mentioned, when checking whether the string ‘kimtaeng’ exists in the String Constant Pool, since the string already exists, the same reference value was returned, and the comparison shows that the reference values are now the same.

Immutability

String literals are immutable constants. Due to this characteristic, if strings reference the same value, they can reference the same object (in the constant pool).

In the code below, if someObject is declared using the literal method rather than the new operator, it will reference the same object as someLiteral.

String someLiteral = "kimtaeng";

String someObject = new String("kimtaeng");

String weAreSameRef = "kimtaeng"; // References the same object as someLiteral

When Java source files (.java) are compiled into class files (.class) and loaded into the JVM (Java Virtual Machine), the JVM checks if the same string (kimtaeng in the code above) exists in the String Constant Pool, reuses it if it already exists, and creates a new string if it doesn’t.

Therefore, even if multiple references point to the same string literal, they must be immutable so they don’t affect each other.

Fortunately, since they’re thread-safe, they can be safely shared in multi-threaded environments.

String Optimization

There are considerations when performing operations with immutable String objects. When concatenating strings using the + operator,

instead of modifying existing strings, new string objects are created and those objects are referenced.

Therefore, existing strings lose their references and become eligible for Garbage Collector collection.

However, starting with Java 5, String concatenation was optimized to internally use StringBuilder.

String Constant Pool

The constant pool (String Constant Pool) location was moved from the Perm area to the Heap area starting with Java 7.

Since the Perm area has a fixed size that cannot be changed at runtime, frequent calls to the intern method could

lead to insufficient storage space, risking OOM (Out Of Memory) issues.

After moving to the Heap area, strings in the constant pool also become eligible for Garbage Collection.

Related Link) JDK-6962931 : move interned strings out of the perm gen(Oracle Java Bug Database)

In Java 7, the constant pool’s location was moved from the Perm area (more accurately, Permanent Generation) to the Heap.

Later, in Java 8, the Perm area was completely removed and replaced by a region called MetaSpace.